This week was my turn to get out and about down here on the ice. Winter trips are a good chance to see more of the sights a bit further away from base. Halley 6 is built on an ice shelf. Now you would think a floating shelf of ice would be fairly flat and regular but not so, and for my winter trip I went off closer to the continent proper to get a better look.

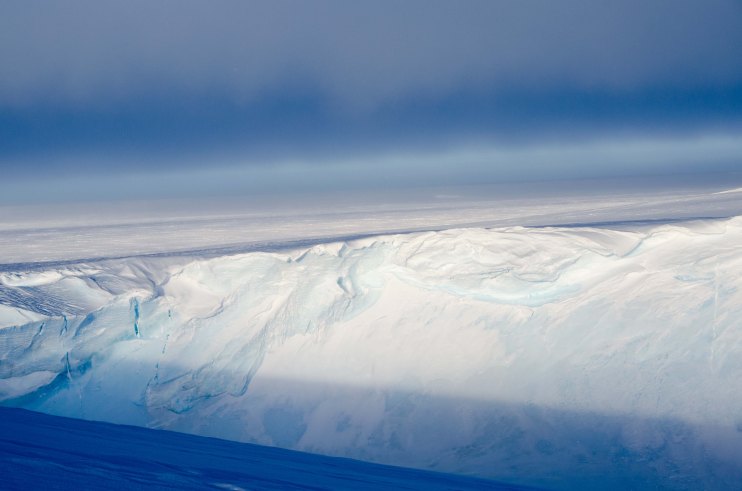

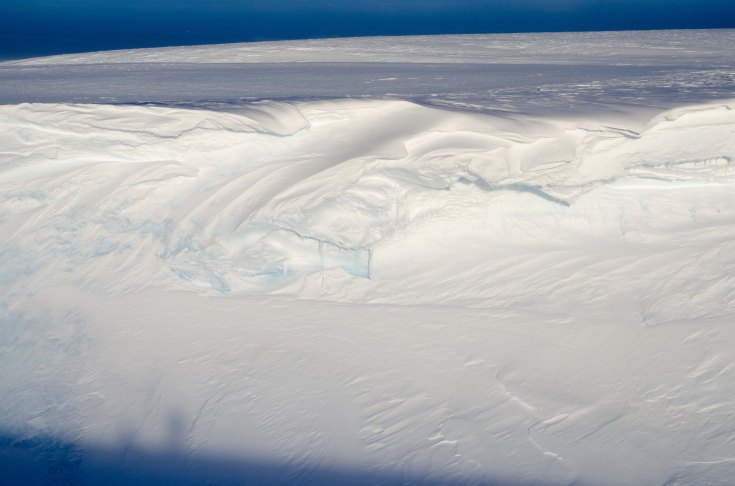

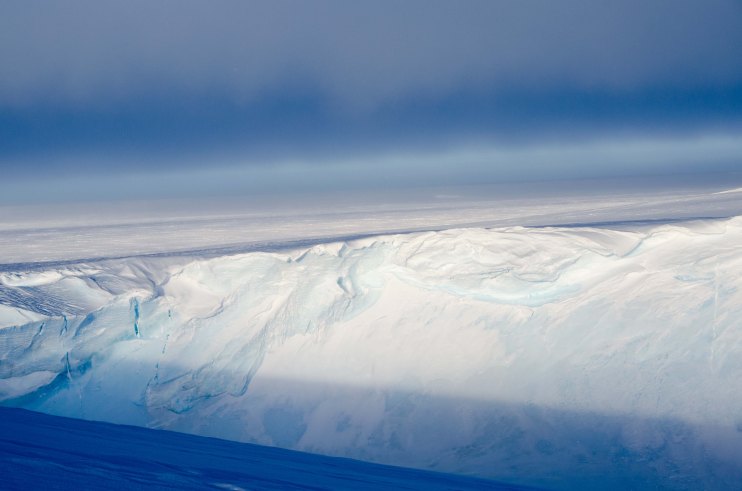

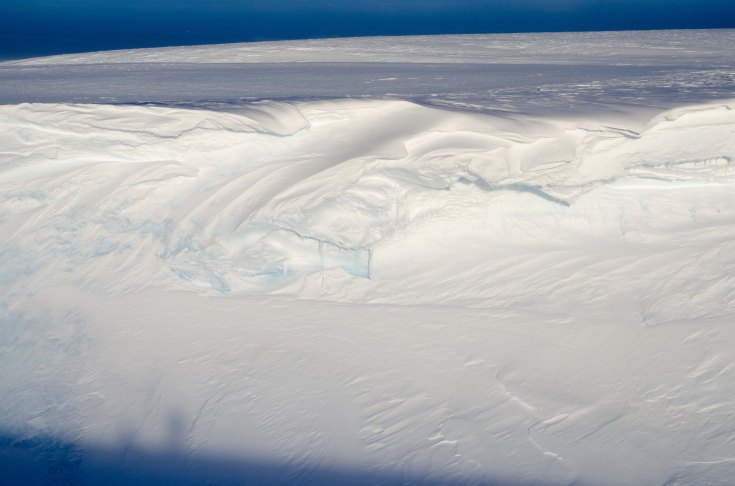

The ice that builds up on the Antarctic continent is a vast sheet that contains most of the earths fresh water. The snow falls and never melts, building up sheets over hundreds of thousands of years, in some places the ice can be five kilometres thick. This ice flows outwards to the coast, spilling out onto the surrounding sea and floating (mostly) off for sometimes hundreds of miles. As the ice leaves the continent it speeds up and the stresses placed on it lead to huge geological features, with cracks and eruptions occurring all over the place. The edge of the continenet, where the ic sheet floats off and becomes an ice shelf is called “The Hinge Zone” . Which is prett cool because I can now talk of my “adventures in the Hinge Zone” when I get back. Not only is the ice moving off the continent it will also move up and down as it sits in the ice.

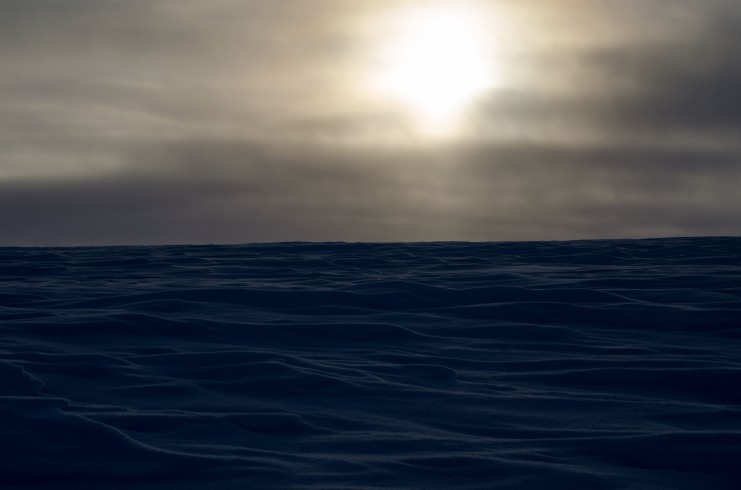

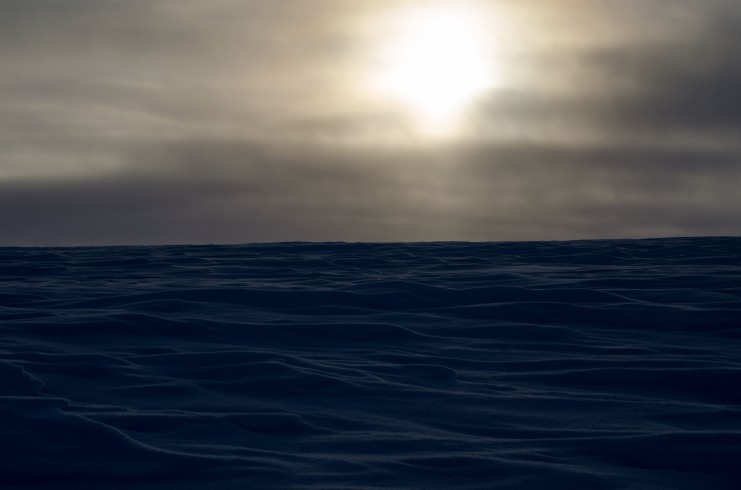

Halley 6 is built on a part of the ice that is relatively stable and flat, but not too far away from base and all this changes, indeed as we are moving at around a metre a day the new Halley 6 base has replaced the old Halley 5 that was on the wrong side of an opening-up fault line that could break off at any moment. Anyway, as you get away from base it becomes a lot more dangerous out there, with the area riddled with crevasses hidden under the accumulated snow. Also this week, the temperature dropped down to around thirty below with the wind chill taking things down to near fifty, raising the fun factor a bit more. Away in the field this cold can be pretty tough, it makes getting anything done ridiculously hard and often pain is only a moment away. Just putting your boots on in the morning without the comfort of a nice dry boot room can quickly be a bit of a mission that ends up with you whirling your arms about like a windmill (to get some warm blood in em – not just for the laugh) with your fingers screaming for warmth. The rewards of being out in such conditions though were with us all week. The whole week the cold air was laden with ice crystals that not only dance and flash in front of your face but lead to amazing atmospheric displays like the one above. From morning till night (and sometimes on into that) the sky was full of beams of light going up, light going down and going sideways, surrounded by halos, rainbows and arches as we wandered, climbed and absailed into the frozen landscape.

Our band of three set off from base on Monday ready for our week away. The winter trips provide a bit of a holiday away from base but also, more importantly allow us to train and hone our skills out in the field. With me were Gerrard our chef and Al the field assistant. Al is the expert in the field, the man with the skills to keep us alive and the skills to teach and Gerrard has been south many times and hence knows a good bit too, so as the newbie ice-boy I knew I was in for a good week.

We travel by skidoo with Nansen sledges towed behind loaded up with tents, food and anything we might need in an emergency- and enough to keep us going should the weather prevent us from getting back for quite a while, something that often happens down here. We do so roped together so that if the worst occurred and one of us did go into a slot in the ice the results wouldn’t be too horrific. Our fist major feature is The Gatekeeper. A huge depression in the ice surrounded by smaller crevasses. Gatekeeper is a crack in the ice that has widened out into a bit of a canyon that then narrows in the middle. In this middle section the two outer walls are near enough together for snow to build up forming a bridge. It was this bridge that we crossed. Now, despite Al’s assurance that the bridge was bomb-proof I still confess to holding my breath as we went over. All done safely we then made our way on to Aladdins – a huge chunk of ice that has detached from the sheet and got turned and thrust up by the movement of the ice. This was to be the location of our base camp.

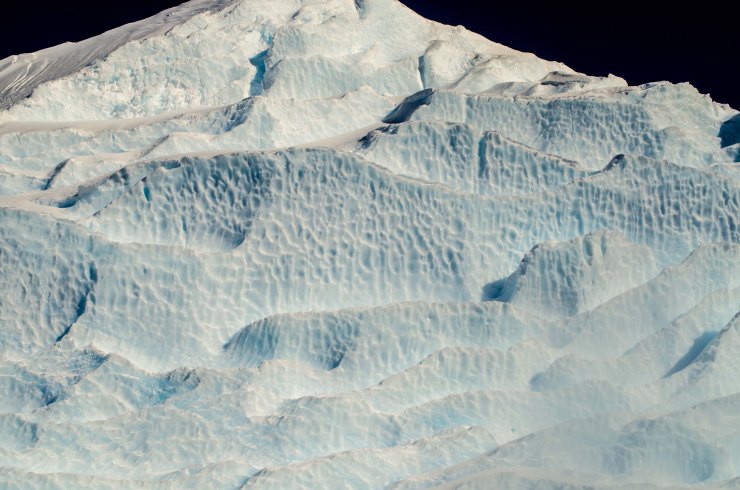

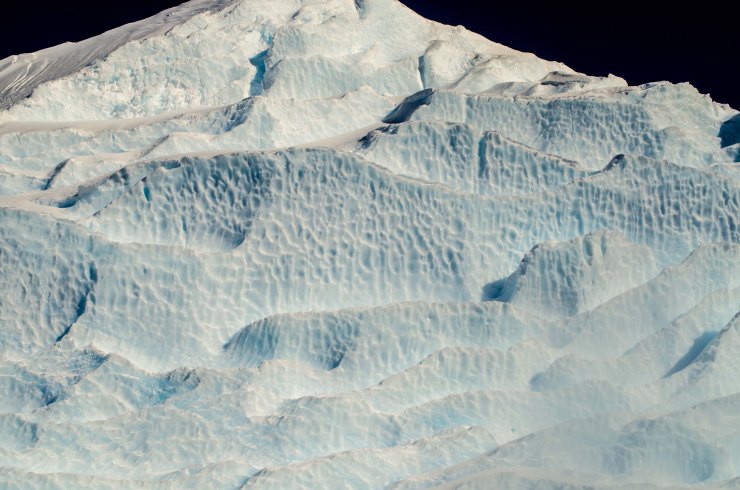

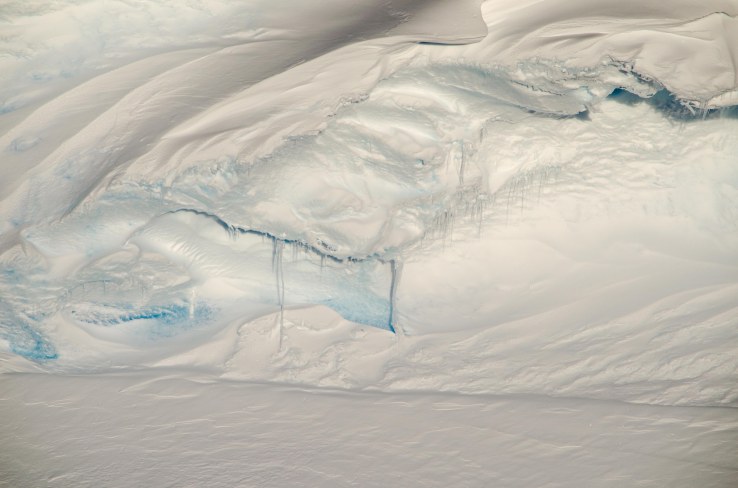

We set up camp with the pyramid tent as our new home for the week, covered the skidoos with a tarp, set up the radio array and got ready to have a quick explore of our immediate vicinity (after a cup of tea). The cold, as long as you were properly dressed (it’s the getting properly dressed that hurts) was not too bad so we geared up, with crampons, harness and tonnes of other gear and set off for a quick wander. The area we had camped in was a kilometre wide depression in the surrounding ice, with huge strips of ice that looked like levees or dykes surrounding our little valley floor. In this valley floor is Alladins. A huge chunk of ice pointing upwards above the surrounding area with what seems like a moat around it. The moat is an area where the sections of ice are separated and the wind has gouged out huge channels in these areas of weakness, leaving a labyrinth of passages and gulleys that are walled on either side by cornices of snow that look set to collapse under their own weight. The wind sculpts the snow and ice giving some of it the look of a gigantic dessert like ice cream or merengue, whilst other areas are hard, almost stone like but still with something organic looking about them, like huge walls that seem to be made out of glowing blue fish scales.

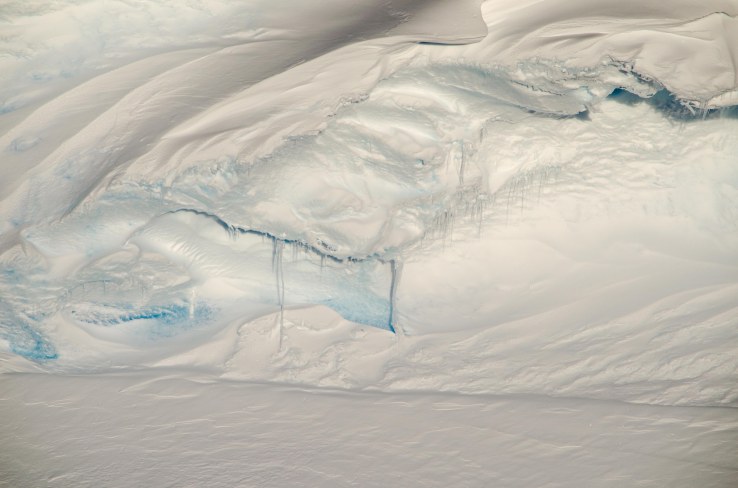

The next few days are spent exploring this odd canyon surrounding Alladins, which winds its way round and round. Some of it is walkable, some not so much. There are many parts where the ropes and harnesses are made use of and we climb down or up to get further in. Although this can be quite painful- removing your thick, outer gloves to un-screw carabiners or feed ropes into belays, the destinations really are worth it. Scooped out of the ice in one area is what appears to be a frozen lake. A smooth surface of blue ice that occasionally shows cracks forced up by the pressure of the surrounding ice, like a miniature version of plate tectonics, or indeed a miniature version of what is going on all around us with the actual ice sheets and shelves. Smashed onto this frozen lake is the debris of cornices and over-hangs that have gotten too big and fallen down, leaving stone-like blue chunks sat on top of the clear surface.

The frozen lake is obviously nothing of the sort but rather ice that is harder than what was above it. This has been then been scoured by the brutal winds coming off the continent. To me though, cresting the ridge and seeing it, you straight away think of a mountain lake frozen for the winter instead of snow that has been compacted over millennia.

After skirting round the many channels and passages created by the wind we climbed to the top of the huge central block of ice, where there is a kind of plateau. Here you can see for miles in every direction and see all the smaller features dotted all around. On and around this plateau you can see similar wind features that we see back at base, Sastrugi, to give them their proper name, are the hard-ice ridges and windtails formed as the ice is at turns blown together and then eroded away again. But, amongst the familiar windtails and mini-waves of ice are long, flat strips of smoother, whiter ice. These are the tell-tale signs that underneath is something other than just older, solid ice. Instead, this is what a crevasse with fresh snow filling in the very top of the gap looks like. The three of us were now roped together as we travelled – in the same way the skidoos were, so that, were one of us to slip into a slot we could be pulled out again. My foot slipped into one of the smaller, more well hidden ones and it was a bit of a heart stopping moment, seeing the empty space under your boot that was once seemingly solid. In the centre of the plateau was a wider crevasse running from one end to the other. This we had christened Al’s crack. Peering down into it you couldn’t see the bottom, just progressively deeper and deeper blue. Into this chasm I went – along with all my climbing gear and a couple of ice axes attached to my harness (but unfortunately no camera). Being down in a crevasse is quite surreal. There is no sound and all hint of wind is gone, leaving you feeling relatively warm and almost serene. After plunging down into the ice as far as the rope would allow I wedged myself between the two walls and just sat for a bit, having a little think. It’s something to behold sat there, way down in this deep blue interior. If it wasn’t for the climb back out I would have been feeling very relaxed when I got back to the surface. Instead I was a bit knackered -to get out I had to climb out with crampons and axes. Now I’ve been climbing before, I’m relatively fit and had assumed Ice climbing to be the same or maybe even slightly easier than other climbing – after all you have two big handles to grab onto. As it happens though, climbing with axes uses muscles in the arms that I wasn’t even aware of having. By the time I made it out I had burning in my arms like I’d never felt before. It took a bit of laying flat on the ice making slightly pathetic noises until I felt able to sling my rucksack back on again.

After climbing and walking around various features for a few days we decided to head down to what is known as Stony Berg. This is a large chunk of ice that has separated from the main sheet and been flipped completely over. The top of it is now covered in stone that has been gouged out of the Antarctic continent as the ice sheet flowed downwards toward the sea. Rocks of all different colours from black basalt to whiter quartz type ones, from huge boulders to smaller pebbles are now visible in the ice. The snow then piles on top of these stones and boulders. When the sun passes through the first few inches of snow above these though, the darker objects below absorb more heat creating a void above them. This means that when you walk on stony berg your feet sink through to the rocks below in the same way you would if you stepped onto the top of a crevasse, a pretty freaky experience. Seeing as this is probably the closet I’ll get to terra-firma for quite a while I was keen to go. This was a place a few of the other people on base had been to. They, however, had gone on skidoos. We would be different. Gerrard is quite keen on nordic skiing and Al fancied a bit of a ski too, so I agreed, probably without really knowing what I was letting myself in for. A bit back I posted about doing a Marathon. Well, I never managed to get that done due to technical issues on base, I did carry on training though and I’m keen to do it next year. But despite being in fairly good nick this was a bit of a shock. I’ve been downhill skiing a few times but I’m not what you’d call good at it and as far as skiing on the flat goes I really didn’t have a clue. The first half an hour I was wondering how the skis actually made this form of travel better, instead they just seemed to be a way of making walking harder. By about five kilometres in I was begining to get the hang of it though, it’s kind of like a grown up version of sliding on a polished floor with just your socks on. But colder. And with really long feet.

It took us six hours of travel across crusty ice and sastrugi carrying full rucksacks of emergency supplies, ropes and fully laden climbing harnesses. Like ice-climbing, this type of exercise used muscles I didn’t even know I had. I’m still sore now but those back on base were fairly impressed with our efforts. I reckon a marathon will be a doddle now, especially in the relatively tropical heat of next summer.

I’ve rambled enough for now so I’ll just post a load of pictures, not really in any order, just some of the cool stuff I’ve seen out and about in the Antarctic wilderness when I could face the pain of getting my fingers just naked enough to operate the camera.

Yeah, I know there’s a lot of em but everyone likes photos don’t they?

I’m absolutely knackered but I cant wait for my next trip out. In the mean time I’ll be practising my ski-touring and ice-climbing. As always, forgive any mistakes for a few days till i get the post and the pics ironed out! Especially ones with the letter P in them- the P button has seized up on my computer!